About 6 months ago, CityLit Project reached out to me about curating and hosting an all-Asian discussion panel at the Baltimore Book Festival. In June 2018, I wrote an article called “Where Are All The Asian Beach Reads?” and I wanted to continue building on that topic.

Year after year, all the Asian contemporary fiction is always these really dramatic, heavy, and let’s just say it -- tragic, immigrant stories. Where’s the fun? Where are the lighthearted reads we can just lose ourselves in and propel ourselves through? And what about second and third generation Asian Americans who have been here our whole lives? Even though statistically, most Asian Americans are first generation immigrants, there are still a huge number of us who grew up as Americans and can’t relate to that story anymore. And yes, these are all great stories that deserve to be told but let’s face it, not many of them will fit into the beach read genre.

So what is a beach read? It’s contemporary fiction or commercial fiction, as they call it in the industry. Beach reads tend to veer towards the chick lit genre but for the purposes of my discussion panel, I broadened the definition to mean all middlebrow literature and included young adult novels as well (e.g. Crazy Rich Asians, The Incendiaries, To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before).

If you’re new to the term, middlebrow is one of three cultural brows that critics like to use to explain and classify forms of culture. There is highbrow (academic and intellectual) and lowbrow (think celebrity memoirs and trashy reality TV shows like Jersey Shore). Middlebrow culture gets dismissed a lot by intellectuals and academics but it shouldn’t — there is a lot of importance in it. Middlebrow culture is how you determine the cultural baseline. When I think about middlebrow, I think of novels like The Godfather, Gone Girl, Valley of the Dolls, and Jaws and how much they changed the cultural landscape of the time. Crazy Rich Asians is an example of a middlebrow novel that is doing the same thing right now. The ripple effect from that novel and film will be felt for years.

Why was there such a dearth of middlebrow, fun, lighthearted novels in Asian American literature for decades? There are three main themes that defined Asian American literature for decades before Crazy Rich Asians came along and they were all tragic, weighty and serious:

Immigration stories

Generational divides

Identity politics

In the 90s, after Amy Tan found tremendous success in the literary world and Hollywood with the The Joy Luck Club, Asian American Studies courses started to be taken more seriously in colleges. And because of the novel’s commercial and critical success, a lot of Asian writers who grew up in that era felt a lot of pressure to write those same themes. Publishers wanted to replicate it and repeat the same story over and over again. What ended up happening was that Asian writers didn’t feel like they were allowed to talk about anything else if they didn’t cover at least one of those themes and still be considered an Asian American writer. I blame the publishing industry for applying a lot of that pressure on those writers and making it extremely difficult for Asian writers to write about anything else. I also blame the publishing industry for forcing the Asian American genre to be defined as one of trauma, oppression and isolation.

I predict YA (Young Adult — ages 12-18) and MG (Middle Grade — ages 8-12) literature is going to see an explosion of Asian American stories in the near future. And it is a trend that I think will continue for years. With anime, k-dramas, reality shows like Terrace House, BTS, and k-beauty breaking into the mainstream these past few years, I think this demographic will be the quickest to give voice to the most diverse stories and authors.

YA is a genre that has always been indivisible of politics and activism and for good reason. YA and MG literature also encompass a lot of beach reads since students tend to read for fun more during their summer months. When people think of YA and MG novels, they tend to think of Harry Potter and Twilight. But these genres have always been on the forefront of the cultural baseline. When I think about the ongoing and absolutely savage social media debates that have been going on for the past 5 or 6 years -- the battles between the progressive left and the alt-right, the defining themes of racial and sexual identity, class, gender, free speech, police brutality, anti-blackness and colorism in the Asian community -- these are all being explored in YA and MG novels. (Keith Stuart, Youth Now)

Giving a young person the right book at the right time can really be life-changing. For me, it was reading The Joy Luck Club in 6th grade. Stories can be really powerful and used as a force for positive change. And young people, most of all, are open to challenging old ideas, beliefs and social injustice.

I think we need to be more careful when criticizing Asian authors if we don’t like their work. I’m not talking about writing characters that are like Long Duk Dong in Sixteen Candles or Leslie Chow in The Hangover. Go ahead and trash that kind of careless and regressive writing. I’m talking about backlash to any Asian writer who faces claims that they are “sellouts,” that they “don’t represent the community” and “should be shut down” or “boycotted.” I honestly think that the burden and pressure will just drive a lot of Asian authors to abandon writing Asian stories altogether. We want more Asian stories, not less. I mean, the ultimate goal when it comes to more representation is to fight less and celebrate more, right?. Writing novels is a great way to ask all kinds of political questions and create empathy for other people’s experiences.

*Special thanks to my panelists: Sunny Reed of A Critical Discourse, Chris Jesu Lee aka Oxford Kondo of Plan A Magazine and The Escape from Plan A Podcast, Jemarc Axinto of The Gamer Guide and The Nerds of Color, and Vanessa Ulrich of The Primpy Sheep.

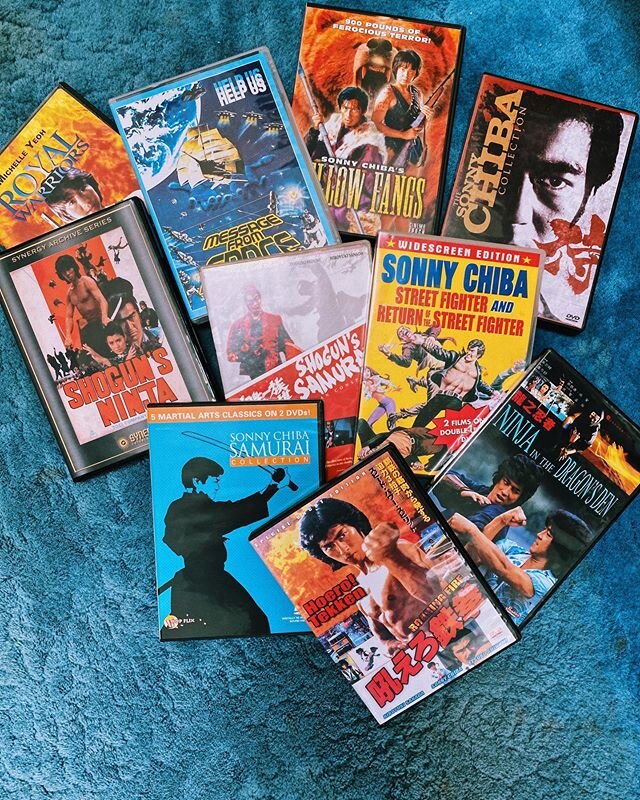

I usually do a write up of the events I’ve organized or hosted and my most-read articles at the end of the year. This was an unusual year (obviously, there is no need to go into it here) so I didn’t bother. Instead I want to highlight a project of mine that I am particularly proud of — it’s my new podcast show, Unverified Accounts, that I cohost with my frequent collaborators, Chris Jesu Lee and Filip Guo. If you're a big movie/TV/book buff, have leftist sympathies, but can't stand 'wokeness' dumbing down our culture, then we're the podcast for you. So far in our 25 episodes, we’ve covered a range of contentious topics.