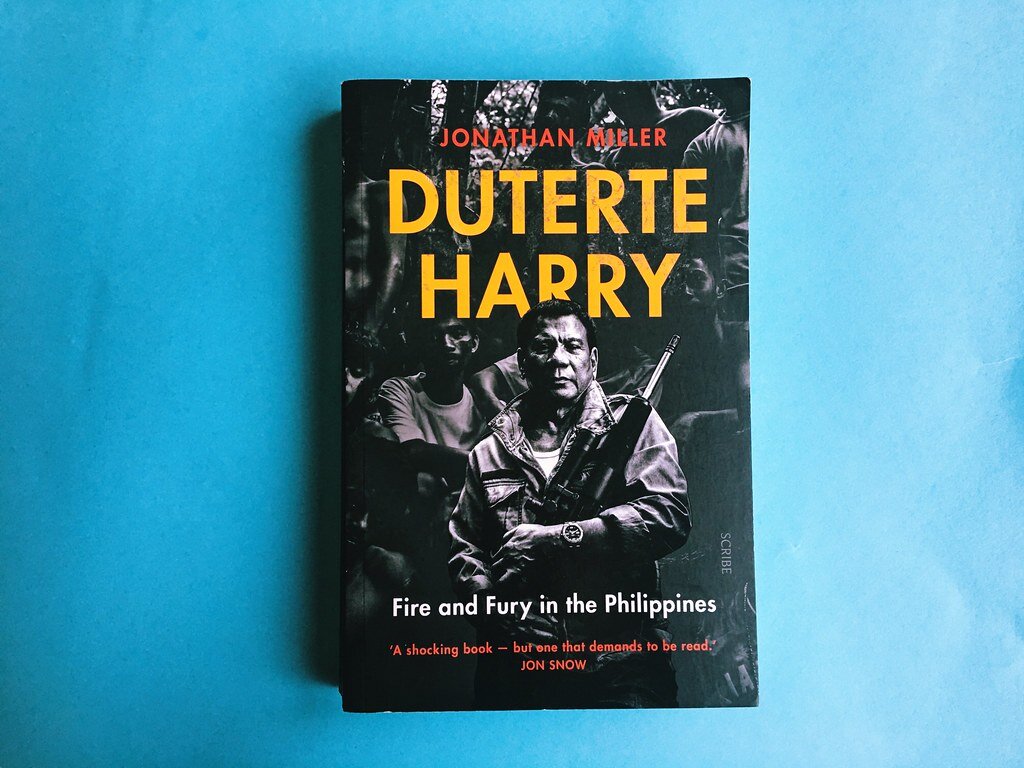

By this point, President Rodrigo Duterte might be the most famous Filipino president, after Ferdinand Marcos. If you pay attention to the news, then you know this much about him: He’s a colorful orator and has managed to insult Pope Francis, Barack Obama, the European Union, and even Jonathan Miller himself, who was raised in Southeast Asia and serves as the foreign correspondent for Channel 4 News in the UK and is the author of a new biography, Rodrigo Duterte: Fire and Fury in the Philippines. (I actually prefer its UK title:,Duterte Harry: Fire and Fury in the Philippines.)

President Duterte has what many former Philippine presidents lacked: anti-imperialist anger against the Spanish colonizers and their abusive Catholic priests and anger against the glaring hypocrisy of the United States. Deferential is not a characteristic associated with Duterte.

This is also a man who publicly compared himself to Idi Amin.

But the main reason for his fame (or infamy) is his remedy for the crime and corruption that run rampant in many parts of the Philippines. I’ve written before that I have a really hard time forming an opinion about President Duterte and I often feel like it's just not my place to anyway. His approval rating remains consistently high - it was at almost 82% in January and February of this year (possibly the result of his keyboard army campaign to inflate his popularity). Outside of the Philippines however, he has faced a lot of international criticism of his human rights record coupled with threats of United Nations investigations into all of the extrajudicial killings happening.

So, why is the Philippines' war on drugs different from the American war on drugs? One thing that makes it different is that Duterte doesn't make a distinction between the addict and the drug dealer. Westerners and especially Americans tend to be very sympathetic towards drug addicts because we see them as victims. We're much more aggressive towards drug dealers and bosses. Duterte doesn't make a distinction between the two groups of people and there is a very famous quote of him saying, "These 3 million addicts that are in my country, I would kill them all if I could." You can see he's clearly saying addict, not dealer. He has also been quoted as saying, "These addicts, their parents don't have the heart to kill them because it's too painful to kill your own child, so you have to kill them." One can easily see how he is encouraging extrajudicial killings with a lack of due process and trials.

This war on drugs gets a lot of international press because it is so controversial and foreign from a western perspective. We don't tend to think that crimes like dealing drugs or possessing drugs is deserving of a death sentence, but he does.

Meanwhile, Duterte has created a culture of fear among the people in his country. He will have his police force and military get together and create these lists of suspected drug users, criminals, drug dealers, and government officials who they suspect are working with the drug dealers and they'll give the list to a community and they will read the names on TV and say, these people have a certain amount of time to turn themselves in.

If you're unfamiliar with Filipino politics, then you are probably wondering how Duterte was elected to the presidency. Prior to the presidency, he was the mayor of a town in the southern Philippines where crime was high because of insurgency, drugs, gangs, and rebellion, and because of his policies, crime was at an all-time low. He campaigned on that, with a lot of his supporters believing he could accomplish the same thing at the national level.

At one point in his biography, Miller recounts a story where Duterte had called him “putang ina mo” (translation: son of a whore) at a press conference because he thought Miller was an American journalist. Later, when it was revealed to him that Miller was actually a British nationalist, Duterte held out his hand and apologized. For Duterte, branding someone an American was a far more grievous insult than calling somebody’s mother a whore.

Right from the opening chapters, Miller spells out what the people of the Philippines are dealing with in President Rodrigo Duterte -- a “narcissistic revenge fantasy superhero come to life.”

Let’s hear what Jonathan Miller has to say about him…

President Rodrigo Duterte / Photo from Esquire Philippines

You mention in the book that journalists really enjoy covering Duterte. Can you talk a little bit about that phenomenon and how it’s affected media coverage in the Philippines and abroad? Do you feel that this adds to the sensationalized view of Duterte? What are the pros and cons of it?

At the beginning, I did indeed enjoy covering Duterte. He was such an iconoclast — “colourful” as Obama put it. He certainly wasn’t a beige politician. As jaws dropped around the world each time he opened his mouth, the shock value made great copy and lively TV. Filipinos loved him because here, finally (they thought) as a straight-talking man-of-the-people who was not prepared to pander to liberal sensitivities or kowtow to America. Around the world, he made headlines for his outspoken, un-PC views and wild boasts. In my book I talk of how every fresh profanity directed at world leaders would prompt demands for ‘more Duterte’ from my London newsroom… but it did not take long for me to learn that he was an altogether darker, more menacing figure than the entertaining cardboard cutout loudmouth he was portrayed as abroad. The sensationalised view of Duterte, which certainly put the Philippines on the map and which we journalists were guilty of perpetuating, masked the gravity of what he quickly began to do as president. He wasted no time in launching a Latin America-style dirty war against drugs involving thousands of extrajudicial killings and he systematically began to dismantle the pillars of Asia’s oldest democracy.

We’ve got a Filipino leader who is increasingly on the world stage. Is the coverage for good reasons or is it just because he’s so controversial and can bring a lot of clicks? How has his fame affected the world view of the Philippines in general?

Duterte is sort of news clickbait, yes. In my view he got a lot of coverage simply because he was so controversial. It’s less ‘fame’ and more notoriety though. He did not grab headlines because he had any enlightened policies. His only policy of note was his programme to kill drug addicts and dealers. You describe him as a leader “increasingly on the world stage” — but I’m not sure I agree with you there. He certainly entered the political arena with great fanfare and his crude language — even directed at the Pope — and violent policies drew much international attention, but as a foreign correspondent based in Southeast Asia, I’ve noticed how international coverage of Duterte has faded with time. Across the world, people just got used to him: it’s not that the killings tailed off — they didn’t. They just weren’t reported as much. But people are still being gunned down every day. And it’s not that the intimidation of his opponents ended — that didn’t stop either… in fact, as I write, news has just broken that his most outspoken critic in the senate, Sonny Trillanes, who I spoke to at length in my research, has been arrested. Duterte's sister told me how as a child he would “get away with murder.” He still does — metaphorically and literally.

Duterte’s war on drugs has been compared to the situation in Latin America -- Colombia and Mexico, to be precise. What do you make of those comparisons?

It’s a false comparison, no matter how much Duterte talks up the notion of his waging a Latin America-style drugs war, it’s not. He might have sent his Chief of Police to Colombia, but Australia has a far worse crystal meth addiction crisis than the Philippines and they don’t go around gunning down addicts. Duterte has knowingly exaggerated the scale of what he called the drugs ‘pandemic’ — in reality there are, according to the Philippines Dangerous Drugs Board, a fraction of the “four or five million” addicts Duterte claims. Yes there is a drug addiction problem and yes, shabu is being cooked in the Philippines, but it’s nowhere near as serious a problem as he makes out. In an opinion piece in The New York Times, Cesar Gaviria, who, as President of Colombia in the early 1990s had overseen the hunt for Pablo Escobar, wrote that throwing more soldiers and police at drug users was not just a waste of time but would make the problem worse. His article was titled: “President Duterte is Repeating My Mistakes.” ‘Trust me,' he said, addressing Duterte directly, ‘I learned the hard way… the war on drugs is essentially a war on people.’

You’ve mentioned that Duterte’s language distracts from the real issues at hand. There is so much media coverage on his “bugoy,” his gangster style of talking and carrying himself. Do you think it takes away from what is really important?

Yes. The ‘gangster charm’ thing blinded Filipinos and many abroad to the seriousness of what he’s doing — things which many I’ve spoken to say will take the country will take decades to recover from. What’s disarming and attractive about Duterte is his extreme informality, his unstatesmanlike style and self-depcricating manner. He’ll often mock his own lacklustre academic performance, for example. People warm to that in the way that they laugh at his crude invective — even when it’s about subjects as serious as rape. But Duterte has conned people with his carefully cultivated ‘bugoy’ — or hoodlum —image. He is not a bad-ass kid from the slums of Davao: he was the son of the Governor of Davao who learned his spicy vocabulary, his misogynistic manners and developed his love of firearms from his bodyguards. He was a child of privilege. A spoiled brat. So he knows exactly what he’s doing when he deploys his Duterte Harry persona. It worked for him as the Mayor of Davao and it’s worked for him as President of the Philippines.

Something I’ve picked up on is that my family here in the US hates him but some of my family in the Philippines adores him. A lot of people are like that. Why do you think there is such a difference in how he is viewed?

In the UK we’d say he’s like Marmite (a revolting yeast extract spread) — which people either love or loathe. I noticed in one of your blogs that you describe Duterte as “an extremely controversial and polarising figure” but say you have a really hard time forming an opinion about him and feel it may not be your place to do so anyway. You add that he is very misunderstood to Americans and Westerners. If Duterte is viewed abroad as an entertaining, one-dimentional, populist maverick, it’s to some degree the fault of the foreign press in projecting that image of him. But I think Duterte was misunderstood even more by Filipinos at home. The 16.6-million who voted for him bought into his propaganda — and they were lied to. He lied about his past achievements in the way that he lied about the scale of the drugs problem. Don’t forget that although he won by a landslide, there were many millions of Filipinos who did not vote for him and as time has gone by, they have made their presence increasingly felt. One interesting group of voters are the OFWs, millions of whom voted for him believing his promises that he would clean up on crime and keep their loved ones safe. The opposite has happened: the poor have been the victims in Duterte’s war on drugs. Yet Duterte continues to cultivate OFWs on his trips abroad and they continue to flock to him. Don’t forget that although he won by a landslide, there were many millions of Filipinos who did not vote for him and as time has gone by, they have made their presence increasingly felt.

Why do you think Filipinos have such a liking for what I often hear referred to as “strong men” like Duterte and Trump? Both men have such high approval ratings in the Philippines.

It’s hard to fathom, I must say. Perhaps it’s because they’ve endured so many years of disappointing leadership that when someone comes along and promises to kick ass, people agree that a strongman is exactly what’s needed… and most Filipinos are too young to remember how grim life was under Marcos.

I hear a lot of comparisons between Trump and Duterte, especially when it comes to their social media popularity. What do you make of those?

Well, the American press found an easy journalistic shorthand in christening Duterte “the Trump of Asia.” They certainly have their similarities — mostly down to the fact that both are malignant narcissists and misogynists. A friend of mine suggested to me that Duterte was like Trump’s inner demon. I think that nails it: Duterte out-Trumps Trump and behaves like Trump might if he were completely unleashed. The two men seem to have a genuine rapport, which blossomed into a fully-fledged alpha-male bromance in a summit in Manila in November 2017 when Duterte toasted Trump with champagne and then serenaded him with his favourite balad, Ikaw. I’m sure Filipinos everywhere know its lyrics, which translate into English as “You are the light of my world. You are the love I’ve been waiting for.” It’s handy having an American president who doesn’t “give a shit” about human rights either.

Where do you fall on the notion that he makes Filipinos proud of being Filipino?

The Philippines is a big and astonishingly beautiful country with a population of more than 100 million people… that’s huge! And yet most remain locked in poverty. There is eye-watering inequality. The slums a stone’s throw from the swanky Makati district as as depressingly poor as you’ll find anywhere in the world. There is a sense of righteous indignation that as a nation, Filipinos were so cruelly treated and ruthlessly exploited by violent imperialist powers — first the Spanish, then the US, over five centuries — all in the guise of supposed civilisation. Not many Filipino leaders have expressed the seething anger over this but Duterte tapped into it and stood up and said it straight to an American President. There were many, beyond Mindanao, where the ravages of colonialism were worst-felt, who applauded this. Also, the sheer fact that that Duterte’s brazen style made people laugh and feel good about themselves was, at first, a welcome break from the past. But I had conversations with many Filipinos, some of them prominent names, who confessed the opposite: they said Duterte’s ignorance and boorishness made them shrivel up with embarrassment.

You spoke to an ambulance attendant in Davao, the southern Philippines city where Duterte served as mayor for 25 years before running for president. He said most of the victims of the drug war were dark-skinned and the “poorest of the poor.” You’ve mentioned that those who hate Duterte and those who love him say that what happened in Davao is key to understanding where he’s headed now. Where do you think his administration is headed?

The thesis of my book is that while some describe Duterte as unpredictable, everything that happened was entirely predictable. Duterte’s record as Mayor of Davao City is a case in point. You only need to look at what he did there as mayor, how he behaved and what happened in that city to see that what he has done as president is replicate it on a national scale, turning it into a national franchise. Would Filipinos have voted for him in such numbers if they’d stopped to challenge his assertions that he’d turned Davao into an oasis of peace and solved the drugs problem? It was all nonsense and national crime statistics show that Davao City is still the Philippines’ murder capital; death squads roam the streets, drug addiction is rife, rape is common. In a Davao slum, I met a woman called Clarita Alia, a widow, whose four sons were all murdered by the Davao Death Squad, one after the other. “It started with my sons,” she told me. “It saddens me that they are doing this everywhere now. I saw this coming. I warned them he would do this everywhere.”

Jonathan Miller’s book, Duterte Harry: Fire and Fury in the Philippines was released in the US on September 4th. Get your copy here. Special thanks to Kelly Falconer at the Asia Literary Agency for helping to set up this interview!

I usually do a write up of the events I’ve organized or hosted and my most-read articles at the end of the year. This was an unusual year (obviously, there is no need to go into it here) so I didn’t bother. Instead I want to highlight a project of mine that I am particularly proud of — it’s my new podcast show, Unverified Accounts, that I cohost with my frequent collaborators, Chris Jesu Lee and Filip Guo. If you're a big movie/TV/book buff, have leftist sympathies, but can't stand 'wokeness' dumbing down our culture, then we're the podcast for you. So far in our 25 episodes, we’ve covered a range of contentious topics.